Query Guide

sq implements a jq -style query language, formally

known as SLQ

.

Behind the scenes, all sq queries execute against a SQL database. This is true even for

document sources

such as CSV

or XLSX

. For those document

sources, sq loads the source data into an ingest database

,

and executes the query against that database.

sq’s query language

and execute database-native SQL queries using the sq sql

command.sq query command has many flags. See the sq

command reference

for details.Fundamentals

Let’s take a look at a query that shows the main elements.

$ sq '@sakila_pg | .actor | where(.actor_id < 10) | .first_name, .last_name | .[0:3]'

first_name last_name

PENELOPE GUINESS

NICK WAHLBERG

ED CHASE

You can probably guess what’s going on above. This query has 5 segments:

| Handle | Table | Filter | Column(s) | Row Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

@sakila_pg | .actor | where(.actor_id < 10) | .first_name, .last_name | .[0:3] |

Ultimately the SLQ query is translated to a SQL query, which is executed

against the @sakila_pg source (which in this example is a Postgres

database). The generated SQL query will look something like:

SELECT "first_name", "last_name" FROM "actor"

WHERE "actor_id" < 10

LIMIT 3 OFFSET 0

Shorthand

For a single-table query, you can concatenate the handle and table name.

In this example, we list all the rows of the actor table.

# Longhand

$ sq '@sakila_pg | .actor'

# Shorthand

$ sq '@sakila_pg.actor'

If the query only has a single segment and doesn’t contain any shell delimiters or control chars, you can omit the quotes:

$ sq @sakila_pg.actor

If the query is against the active source , then you don’t even need to specify the handle.

$ sq .actor

You can override the active source

for the current query using the --src

flag, or override the source’s

catalog and/or schema

using --src.schema

,

or even combine the two.

# Query @sakila_pg instead of the active source.

$ sq --src @sakila_pg '.actor'

# Query using the "public" schema of the active source's current catalog.

$ sq --src.schema public '.actor'

# Query using the "public" schema of the active source's "inventory" catalog.

$ sq --src.schema inventory.public '.products'

# Query using the "public" schema of @sakila_pg's "inventory" catalog.

$ sq --src @sakila_pg --src.schema inventory.public '.products'

Filter results (where)

Use the where() mechanism to filter results.

$ sq '.actor | .first_name, .last_name | where(.first_name == "TOM")'

first_name last_name

TOM MCKELLEN

TOM MIRANDA

Ultimately a filter is translated into a SQL WHERE clause such as:

SELECT "first_name", "last_name" FROM "actor" WHERE "first_name" = "TOM"

Operators

The typical comparison operators are available in expressions:

$ sq '.actor | where(.actor_id < 3)'

actor_id first_name last_name last_update

1 PENELOPE GUINESS 2020-06-11T02:50:54Z

2 NICK WAHLBERG 2020-06-11T02:50:54Z

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

== | Equal to |

!= | Not equal to |

< | Less than |

<= | Less than or equal to |

> | Greater than |

>= | Greater than or equal to |

You can use boolean operators (&&, ||) to combine expressions.

$ sq '.actor | where(.actor_id <= 2 || .actor_id == 105)'

actor_id first_name last_name last_update

1 PENELOPE GUINESS 2020-06-11T02:50:54Z

2 NICK WAHLBERG 2020-06-11T02:50:54Z

105 SIDNEY CROWE 2020-06-11T02:50:54Z

For boolean and boolean-like (bit, int) columns, you can compare using true and false literals.

$ sq '.people | where(.is_alive == false)'

name is_alive

Kubla Khan false

$ sq '.people | where(.is_alive == true)'

name is_alive

Kaiser Soze true

Use parentheses to group expressions.

$ sq '.actor | where(.actor_id <= 2 || (.actor_id > 100 && .first_name == "GROUCHO"))'

actor_id first_name last_name last_update

1 PENELOPE GUINESS 2020-06-11T02:50:54Z

2 NICK WAHLBERG 2020-06-11T02:50:54Z

106 GROUCHO DUNST 2020-06-11T02:50:54Z

172 GROUCHO WILLIAMS 2020-06-11T02:50:54Z

Row range

You can limit the number of returned rows using the row range construct .[x:y].

Note that the elements are zero-indexed

.

$ sq '.actor | .[3]' # Return row index 3 (fourth row)

$ sq '.actor | .[0:3]' # Return rows 0-3

$ sq '.actor | .[:3]' # Same as above; return rows 0-3

$ sq '.actor | .[100:]' # Return rows 100 onwards

At the backend, a row range becomes a LIMIT x OFFSET y clause:

SELECT * FROM "actor" LIMIT 3 OFFSET 2

Column aliases

You can give an alias to a column expression using .name:alias.

For example:

$ sq '.actor | .first_name:given_name, .last_name:family_name'

given_name family_name

PENELOPE GUINESS

NICK WAHLBERG

On the backend, sq uses the SQL column AS alias construct. The query

above would be rendered into SQL like this:

SELECT "first_name" AS "given_name", "last_name" AS "family_name" FROM "actor"

This works for any type of column expression, including functions.

$ sq '.actor | count():quantity'

quantity

200

It’s common to alias whitespace names :

$ sq '.actor | ."first name":first_name, ."last name":last_name'

given_name family_name

PENELOPE GUINESS

NICK WAHLBERG

But note that the alias itself can contain whitespace if desired. Simply enclose the alias in double quotes.

$ sq '.actor | .first_name:"First Name"'

First Name

PENELOPE

NICK

Whitespace names

If a table or column name has whitespace, surround the name in quotes.

$ sq '.actor | ."first name", ."last name"'

$ sq '."film actor" | .actor_id'

Select literal

You can select a literal as a column value:

# Postgres source

$ sq '.actor | .first_name, "X", .last_name'

first_name X last_name

PENELOPE X GUINESS

NICK X WAHLBERG

You may want to alias the literal column:

$ sq '.actor | .first_name, "X":middle_name, .last_name'

first_name middle_name last_name

PENELOPE X GUINESS

NICK X WAHLBERG

Select expression

In addition to literals, you can also select expressions. If the

expression does not refer to any column or table, you can omit

the table selector, and use sq as a calculator.

$ sq 1+2

1+2

3

@sakila_pg), the

active source

is used. If there’s no active source,

such as immediately after a new install, sq falls back to using

a temporary DB, typically SQLite.Calculator mode is probably better with --no-header (-H).

$ sq -H 1 + 2 + 3

6

Use parentheses to groups expressions.

$ sq '(1+2)*3'

(1+2)*3

9

You can alias an expression if desired.

$ sq '((1+2)*3):answer'

answer

9

Predefined variables

The --arg flag passes a value to sq as a predefined variable. If you

run sq with --arg foo bar, then $foo is available in the query and

has the value bar. Note that the value will be treated as a string,

so --arg foo 123 will bind $foo to "123".

$ sq --arg first TOM '.actor | where(.first_name == $first)'

actor_id first_name last_name last_update

38 TOM MCKELLEN 2020-06-11T02:50:54Z

42 TOM MIRANDA 2020-06-11T02:50:54Z

This is particularly useful when dealing with values that contain whitespace, shell tokens, long strings, etc..

# Value containing single-quote

$ sq --arg last "O'Toole" '.actor | where(.last_name == $last)'

# Value containing double-quote

sq --arg first 'Elvis "The King"' '.actor | .first_name == $first'

It’s common to combine sq --arg with shell variables:

$ PASSWD=`cat password.txt`

$ sq --arg pw "$PASSWD" '.secrets | where(.password == $pw)'

Note that you can supply multiple variables:

$ sq --arg first TOM --arg last MIRANDA '.actor | where(.first_name == $first && .last_name == $last)'

actor_id first_name last_name last_update

42 TOM MIRANDA 2020-06-11T02:50:54Z

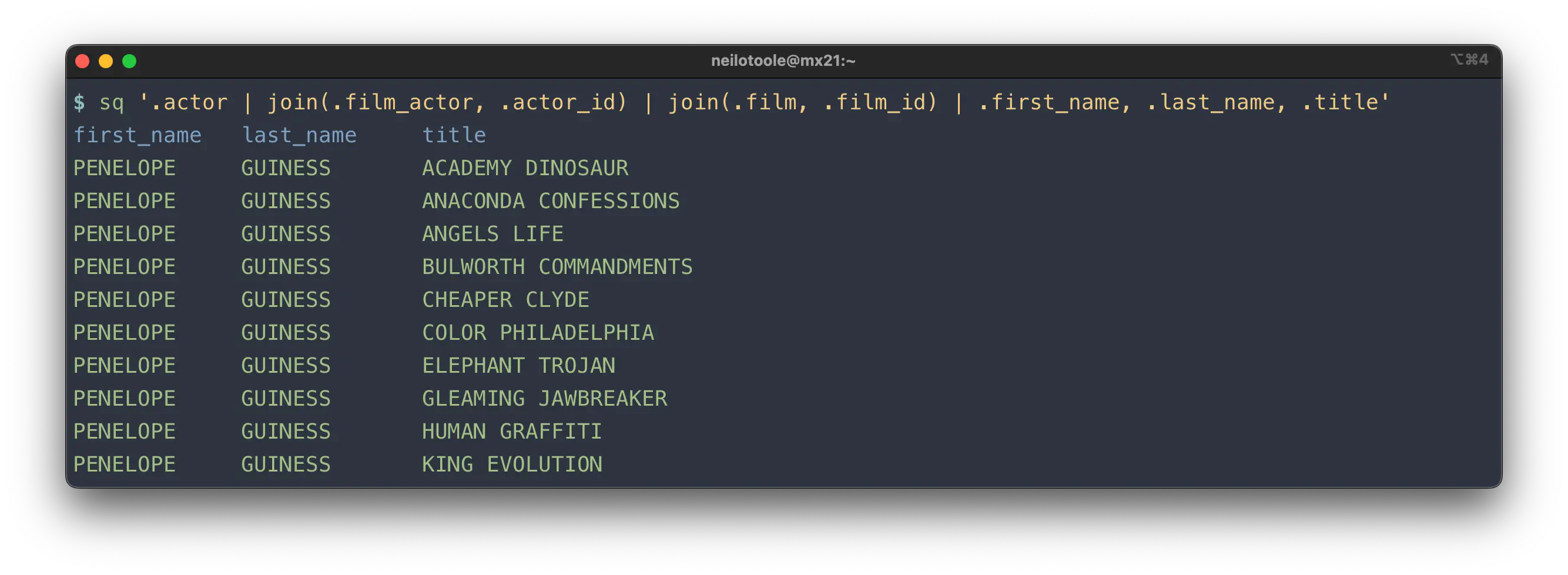

Joins

Use the join construct to join

two or more tables. You can join tables in a

single data source, or across data sources. That is, you can join a Postgres table

and a CSV file, or an Excel worksheet and a JSON file, etc.

Given our Sakila dataset, let’s say we want to get the names of the films

that each actor appears in. The relevant tables here are actor, film_actor,

and film.

In SQL, the join would look like:

SELECT first_name, last_name, title

FROM actor a

INNER JOIN film_actor fa ON a.actor_id = fa.actor_id

INNER JOIN film f ON fa.film_id = f.film_id

The most terse sq query to express this is:

$ sq '.actor | join(.film_actor, .actor_id) | join(.film, .film_id) | .first_name, .last_name, .title'

The general form of a join is:

join_type(.table, predicate_expression)

Join types

The usual SQL join types are supported, except NATURAL JOIN1. Each join

type has a short form and a synonym, e.g. fojoin and full_outer_join. You can use

either form in your query.

| Join type | Synonym | SQL | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

join | inner_join | INNER JOIN | A plain SQL JOIN is actually an INNER JOIN |

ljoin | left_join | LEFT JOIN | |

lojoin | left_outer_join | LEFT OUTER JOIN | |

rjoin | right_join | RIGHT JOIN | |

rojoin | right_outer_join | RIGHT OUTER JOIN | |

fojoin | full_outer_join | FULL OUTER JOIN | Not supported in MySQL |

xjoin | cross_join | CROSS JOIN | Doesn’t take a predicate, e.g. xjoin(.film_actor) |

Join predicate

The join predicate is an expression that renders to the SQL JOIN ... ON x term.

Let’s take our terse example from above.

$ sq '.actor | join(.film_actor, .actor_id) | join(.film, .film_id) | .first_name, .last_name, .title'

The most explicit form of that query would be (linebreaks added for legibility):

$ sq '.actor

| join(.film_actor, .actor.actor_id == .film_actor.actor_id)

| join(.film, .film_actor.film_id == .film.film_id)

| .actor.first_name, .actor.last_name, .film.title'

The query above is obviously needlessly verbose.

Table aliases

We can use table aliases to make the query more legible:

$ sq '.actor:a

| join(.film_actor:fa, .a.actor_id == .fa.actor_id)

| join(.film:f, .fa.film_id == .f.film_id)

| .a.first_name, .a.last_name, .f.title'

Table aliases work like column aliases .

Note that table aliases aren’t restricted to join scenarios. You can generally use them anywhere you reference a table, although it’s often somewhat pointless:

# No table alias

$ sq '.actor | .first_name, .last_name'

# With table alias

$ sq '.actor:a | .a.first_name, .a.last_name'

Unary join predicate

In the common case where tables are joined on equality of identically-named columns, you can simply specify the column name.

# Explicit column equality predicate

$ sq '.actor | join(.film_actor, .actor.actor_id == .film_actor.actor_id)'

# Much better!

$ sq '.actor | join(.film_actor, .actor_id)'

This form is logically equivalent to SQL’s USING(col) mechanism, although

sq chooses to render it using the explicit equality comparison ON tbl1.col = tbl2.col.

Multiple join predicates

The join predicate is an expression, and can feature an arbitrary number of terms. For example:

$ sq '.tbl1 | join(.tbl2, .tbl1.col1 == .tbl2.col1 && .tbl1.col2 != .tbl2.col2)'

This would render to:

SELECT * FROM "tbl1" INNER JOIN "tbl2"

ON "tbl1"."col1" = "tbl2"."col1"

AND "tbl1"."col2" != "tbl2"."col2"

Like any sq expression, you can add parentheses if desired.

$ sq '.tbl1 | join(.tbl2, (.tbl1.col1 == .tbl2.col1) && (.tbl1.col2 != .tbl2.col2))'

No join predicate

CROSS JOIN is the odd man out, in that it doesn’t take a predicate.

$ sq '.film:f | xjoin(.language:l) | .f.title, .l.name'

Cross-source joins

sq can join across two or more data sources. Given three sources:

@sakila/pg12(Postgres)@sakila/my8(MySQL)@sakila/ms17(Microsoft SQL Server)

You can join them as follows:

$ sq '@sakila/pg12.actor

| join(@sakila/my8.film_actor, .actor_id)

| join(@sakila/ms17.film, .film_id)

| .first_name, .last_name, .title'

If there’s an active source (@sakila/pg12 in this example),

you don’t need to qualify the left (first) table:

$ sq '.actor

| join(@sakila/my8.film_actor, .actor_id)

| join(@sakila/ms17.film, .film_id)

| .first_name, .last_name, .title'

If the handle is omitted from any join table reference, the table’s source is assumed to be that of the leftmost table.

$ sq '@sakila/pg12.actor

| join(@sakila/my8.film_actor, .actor_id)

| join(.film, .film_id)

| .first_name, .last_name, .title'

In the example above, the .film table’s source is taken

to be the same as the @sakila/pg12.actor

table’s source, i.e. @sakila/pg12.

With @sakila/pg12 as the active source, this query is equivalent to the above:

$ sq '.actor

| join(@sakila/my8.film_actor, .actor_id)

| join(.film, .film_id)

| .first_name, .last_name, .title'

How do cross-source joins work?

The implementation is very basic (and could be dramatically enhanced). Given a two-source join:

sqcopies the full contents of the left table to the join DB .sqcopies the full contents of the right table to the join DB.sqexecutes the query against the join DB.

Given that this naive implementation perform a full copy of both tables, cross-source joins are only suitable for smaller datasets.

Ambiguous columns

There are two scenarios where column name ambiguity can cause trouble: in the query, and in the result set.

The query below selects the actor_id column, which exists in both the

actor table and the film_actor table. The query will fail.

$ sq '.actor | join(.film_actor, .actor_id) | .first_name, .actor_id'

sq: ... ERROR: column reference "actor_id" is ambiguous (SQLSTATE 42702)

The solution here is to qualify the .actor_id column, using either the

table name, or table alias (if specified).

# Explicitly specify the column's table

$ sq '.actor | join(.film_actor, .actor_id) | .first_name, .actor.actor_id'

# Same, but using table alias

$ sq '.actor:a | join(.film_actor, .actor_id) | .first_name, .a.actor_id'

If you do want the column values from both tables, you can use a column alias:

$ sq '.actor:a | join(.film_actor:fa, .actor_id)

| .first_name, .a.actor_id:a_actor, .fa.actor_id:fa_actor'

first_name a_actor fa_actor

PENELOPE 1 1

What happens if you don’t use a column alias?

$ sq '.actor:a | join(.film_actor:fa, .actor_id) | .first_name, .a.actor_id, .fa.actor_id'

first_name actor_id actor_id_1

PENELOPE 1 1

sq automatically renames duplicate column names in the result set. Thus the

second actor_id column becomes actor_id_1. This is most frequently seen

when executing a SELECT * FROM tbl1 JOIN tbl2: note the actor_id_1 and

last_update_1 columns.

$ sq '.actor | join(.film_actor, .actor_id) | .[0:2]'

actor_id first_name last_name last_update actor_id_1 film_id last_update_1

1 PENELOPE GUINESS 2006-02-15T04:34:33Z 1 1 2006-02-15T05:05:03Z

The renaming behavior is configurable via the result.column.rename

option.

Join examples

# INNER JOIN

$ sq '.actor | join(.film_actor, .actor_id)'

# LEFT JOIN

$ sq '.actor | ljoin(.film_actor, .actor_id)'

# LEFT OUTER JOIN

$ sq '.actor | lojoin(.film_actor, .actor_id)'

# RIGHT JOIN

$ sq '.actor | rjoin(.film_actor, .actor_id)'

# RIGHT OUTER JOIN

$ sq '.actor | rojoin(.film_actor, .actor_id)'

# FULL OUTER JOIN

$ sq '.actor | fojoin(.film_actor, .actor_id)'

# CROSS JOIN

$ sq '.actor | xjoin(.film_actor)'

Functions

avg

avg returns the average of all non-null values of the column.

$ sq '.payment | avg(.amount)'

avg(.amount)

4.2006673312974065

catalog

catalog returns the default catalog

of the DB connection.

See also: schema

.

# Postgres source

$ sq 'catalog()'

sakila

# Switch to SQL Server source

$ sq src @sakila/ms19

$ sq 'schema()'

dbo

catalog honors the --src.schema flag, when used in

the catalog.schema form. For example:

$ sq --src.schema postgres.information_scheam 'catalog(), schema()'

catalog() schema()

postgres public

However, not every driver supports the catalog mechanism fully.

- MySQL treats catalog and schema as somewhat interchangeable

.

It’s a mess. But, looking into

INFORMATION_SCHEMA.SCHEMATA, MySQL listsCATALOG_NAMEasdef(fordefault). Thus, with a MySQL source,catalog()returns the value ofCATALOG_NAME, i.e.def. - SQLite doesn’t support catalogs at all. Nor does it implement

INFORMATION_SCHEMA. Rather than returnNULLor an empty string,sq’s SQLite driver chooses to implementcatalog()by returning the stringdefault.

count

The no-arg count function returns the total number of rows.

$ sq '.actor | count'

count

200

That renders to SQL as:

SELECT count(*) AS "count" FROM "actor"

With an argument, count(.x) returns a count of the number of times

that .x is not null in a group.

# count of non-null values in col first_name

$ sq '.actor | count(.first_name)'

You can also supply an alias:

$ sq '.actor | count:quantity'

quantity

200

count_unique

count_unique counts the unique non-null values of a column.

$ sq '.actor | count_unique(.first_name)'

count_unique(.first_name)

128

group_by

Use group_by to group

results.

$ sq '.payment | .customer_id, sum(.amount) | group_by(.customer_id)'

This translates into:

SELECT "customer_id", sum("amount") FROM "payment" GROUP BY "customer_id"

You can use multiple terms in group_by:

$ sq '.payment | .customer_id, .staff_id, sum(.amount) | group_by(.customer_id, .staff_id)'

You can also use functions inside group_by. For example, to group the payment

amount by month:

$ sq '.payment | _strftime("%Y/%m", .payment_date), sum(.amount) | group_by(_strftime("%Y/%m", .payment_date))'

strftime('%Y/%m', "payment_date") sum("amount")

2005/05 4824.429999999861

2005/06 9631.87999999961

That translates into:

SELECT strftime('%Y/%m', "payment_date"), sum("amount") FROM "payment"

GROUP BY strftime('%Y/%m', "payment_date")

In practice, you probably want to use column aliases :

$ sq '.payment | _strftime("%Y/%m", .payment_date):month, sum(.amount):amount | group_by(.month)'

month amount

2005/05 4824.429999999861

2005/06 9631.87999999961

Note the _strftime function in the example above, and in particular note the

leading underscore. That function is

proprietary

to SQLite

: it won’t work with Postgres,

MySQL etc. sq passes functions through

to the backend, and some of those functions won’t be portable to other data sources.

TLDR: Use proprietary functions with caution.

You can also use the gb synonym for brevity.

$ sq '.payment | .customer_id, sum(.amount) | gb(.customer_id)'

having

Use having to filter results after grouping. The having function must

always be preceded by group_by

.

$ sq '.payment | .customer_id, sum(.amount) |

group_by(.customer_id) | having(sum(.amount) > 180 && sum(.amount) < 195)'

customer_id sum(.amount)

178 194.61

459 186.62

137 194.61

That renders to something like:

SELECT "customer_id", sum("amount") AS "sum(.amount)" FROM "payment"

GROUP BY "customer_id" HAVING sum("amount") > 180 AND sum("amount") < 195

max

max returns the maximum value of the column.

$ sq '.payment | max(.amount)'

max(.amount)

11.99

min

min returns the minimum non-null value of the column.

$ sq '.payment | min(.amount)'

min(.amount)

0

order_by

Use order_by to sort results.

$ sq '.actor | order_by(.first_name)'

actor_id first_name last_name last_update

71 ADAM GRANT 2006-02-15T04:34:33Z

132 ADAM HOPPER 2006-02-15T04:34:33Z

This translates to:

SELECT * FROM "actor" ORDER BY "first_name"

Change the sort order by appending + (ascending) or - (descending)

to the column selector:

$ sq '.actor | order_by(.first_name+, .last_name-)'

actor_id first_name last_name last_update

132 ADAM HOPPER 2006-02-15T04:34:33Z

71 ADAM GRANT 2006-02-15T04:34:33Z

That query becomes:

SELECT * FROM "actor" ORDER BY "first_name" ASC, "last_name" DESC

For interoperability with jq, you can use the

sort_by

synonym:

$ sq '.actor | sort_by(.first_name)'

And there’s also the ob synonym for brevity:

$ sq '.actor | ob(.first_name)'

rownum

rownum returns the one-indexed row number of the current row.

$ sq '.actor | rownum(), .first_name | order_by(.first_name)'

rownum() first_name

1 ADAM

2 ADAM

3 AL

rownum should typically be invoked in conjunction with order_by,

or the order of the rows may be undefined.

It’s trivial to return zero-indexed row numbers: simply subtract 1 from the result.

$ sq '.actor | rownum()-1, .first_name | order_by(.first_name)'

rownum()-1 first_name

0 ADAM

1 ADAM

2 AL

Although, you may want to use a column alias:

$ sq '.actor | rownum()-1:index, .first_name | order_by(.first_name)'

index first_name

0 ADAM

1 ADAM

2 AL

schema

schema returns the default schema

of the DB connection. See also: catalog

.

# Postgres source

$ sq 'schema()'

public

# Switch to SQL Server source

$ sq src @sakila/ms19

$ sq 'schema()'

dbo

schema honors the --src.schema flag, except for SQL Server

.

This is because SQL Server does not permit setting the default

schema on a per-connection basis (it can only be changed per-user). Thus, schema()

always returns the user’s default schema, which is typically dbo.

# Postgres source

$ sq src @sakila/pg12

$ sq --src.schema information_schema 'schema()'

schema()

information_schema

# SQL Server doesn't honor --src.schema

$ sq src @sakila/ms19

$ sq --src.schema information_schema 'schema()'

schema()

dbo

sum

sum returns the sum of all non-null values for the column. If there are no

input rows, null is returned.

$ sq '.payment | sum(.amount)'

sum(.amount)

67416.50999999208

unique

unique filters results, returning only unique values.

# Return only unique first names

$ sq '.actor | .first_name | unique'

The function maps to the SQL DISTINCT keyword:

SELECT DISTINCT "first_name" FROM "actor"

You can also use the uniq synonym:

$ sq '.actor | .first_name | uniq'

Proprietary functions

The standard functions listed above are all portable: that is to say, they

behave (more or less) the same whether the backing DB is Postgres, MySQL, etc.

Portability / compatability is a primary design goal for sq. Over time,

it’s probable that sq’s “standard library” of portable functions will grow.

However, sometimes you simply need to invoke a function that exists only

in Postgres, or SQL Server, etc. To invoke such a function, simply prefix

the proprietary function name with an underscore.

# SQLite "strftime"

$ sq '@sakila | .payment | _strftime("%m", .payment_date)'

# MySQL "date_format"

$ sq '@sakila/mysql | .payment | _date_format(.payment_date, "%m")'

# Postgres "date_trunc" func

$ sq '@sakila/postgres | .payment | _date_trunc("month", .payment_date)'

# SQL Server "month" func

$ sq '@sakila | .payment | _month(.payment_date)'

NATURAL JOINis not implemented, for several reasons. It’s not universally supported (e.g. SQL Server ). It’s considered an anti-pattern by some. And in testing, it doesn’t always work consistently from one DB to the other, leading to user surprise. That said, it’s possible this decision will be reconsidered based on user feedback . ↩︎